Together, In Their Last Moments: Shermaine the Child Life Specialist

Having been one of my closest friends for close to 6 years, I had been looking forward to interviewing Shermaine for the longest time. I've been hearing anecdotes of her time at National University Hospital (NUH) since she started, and jumped at the opportunity to share her experiences.

It did take us a moment to get into the groove of things—we kept bursting into laughter the first time I tried to ask her a serious question. "I can't do this!" "I'm trying!!!", we kept telling one another. Shared laughter: the perfect start to any interview, naturally.

A Bit About Child Life Specialists

"I guess, it's someone who advocates for children in a medical setting. Offering different mediums of play and expression," Shermaine explained, when we finally were able to maintain our composure. "Maybe other people will see us as the person who plays—not entirely wrong, because we really use play as a base medium to interact with children. Because that's the language they speak."

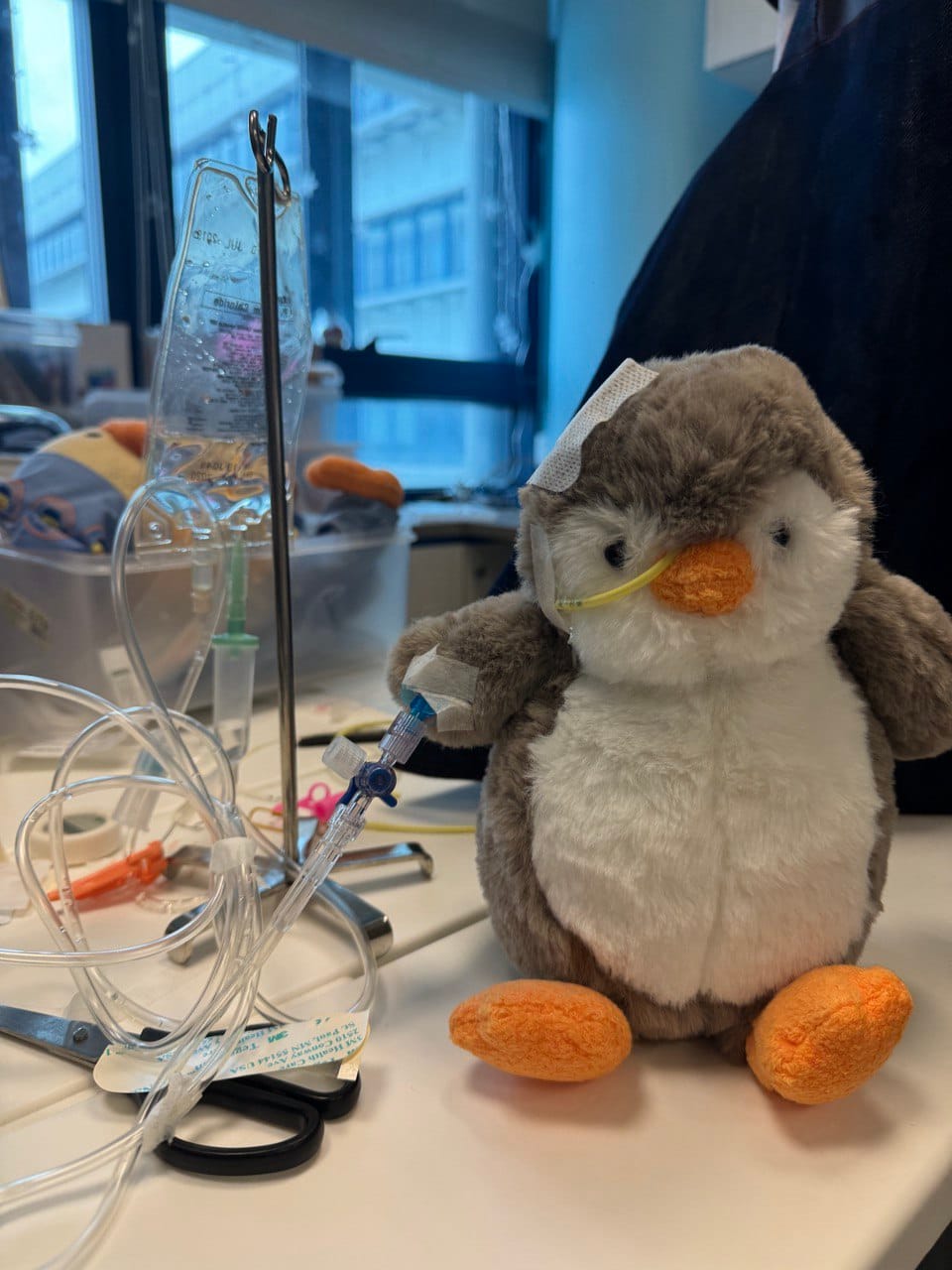

"It's a lot of developmental play for kids who are [staying] prolonged in the hospital; therapeutic play for them to express themselves, to play out their medical experiences. We have medical play to increase their familiarity and adaptation to treatment, having that sense of control and achievement. A sense of empowerment that they are able to be involved in certain things."

Shermaine was first introduced to Child Life Therapy during her first year at SUSS. As she had completed a diploma in an early childhood course, she was offered an alternative placement for her first year practicum, where she ended up in the KKH Child Life Art and Music Therapy, CHAMPS and met her first Child Life mentor.

"I guess, this kind of fitted into the one-to-one interaction that I like. Because I don't have to fit the child into any curriculum. I'm there to meet the children at where he or she is at," Shermaine explained. "So, there's where I get [sic] to meet a lot of, like, social cases. A lot of children that are undergoing treatment. I felt it was something different from being a teacher, but I also need [sic] the relevant skills and knoweldge to fall back on."

"Typically, I start my day with case notes. I try to type down the things that I plan to do for each child," she shared. "I will receive a inpatient list that tells you which are the kids that are warded, the procedures that kid is going through. And then an outpatient list for kids that just come [to the] clinic for full blood count checks or normal medical procedures that [they] don't need to be warded overnight [for]. It's quite flexible in a way. I don't have a fixed timing to see a child. I just got to make sure that I plan my timing accordingly, know who to see and [what to] prep for each child, [the] materials that I will bring along."

"We play a lot to decrease their fear first and [use] a lot of child-friendly terms. Instead of saying, 'needle', we'll just say, 'Oh, it's a sharp item'. Because some injections... can really feel like [it's] burning your muscles... like you think about fire, we just say, 'It's a warm sensation. It feels warm on your stomach.' Those are the things we will say," she articulated.

"We'll use actual syringes, actual IV plugs [and] do it on a medical doll, so they can play out their frustrations or they can play our their fear. From time to time, you will see children... At first, they don't really dare to see. They will want you to be the one playing for them to see," she recounted. "And then, they eventually progress to, 'Oh, can you hold my hand to do it?' and then, eventually, 'No, I can do it myself', because they are already so familiar with the procedure.'

Shermaine also explained how many of the decisions she makes on what to do with each child depended on her understanding and interactions with the children—very much like how we plan for development in the classroom. Some children prefer visual schedules that detail exactly what will happen during a medical procedure; other children don't want to be overwhelmed with all that information.

"I think it helps to reduce the anxiety... Sudden things happening can be very, very fearful for the children. I always believe in making the unknown known for them."

On The Child's Terms

"Maybe to advocate for the children's needs in the medical setting, too," she pondered. "Sometimes, the medical team may be in a rush. They really need to get their checks done. So, sometimes, the way that communicate with children.... may not be the best or the more age-appropriate. And that's where we will come in as Child Life to advocate for the children's needs, like, "Can you please count for the child? Let them know what you're doing?", to reduce that fear and also help doctors and patients bond a little bit more."

"I usually work with children with leukaemia and they have this procedure: intrathecal chemotherapy," she recounted. "Basically, they need to be in a certain position, so that the needle can pass through from this space between your spine, between the bones. [It's] for the medicine fluid to flow through your spine to your brain. That's one of the procedures I usually support."

"[There are] teenagers who don't do it with sedation. So, there'll be a lot of conversations about the things that make them feel comfortable, the things that make them feel safe, the things they would like to do when the procedure is happening. Giving [them] a lot of control over their own coping strategies," she continued. "Some kids will want to continue their TikToks, some kids will want to hold hands. Some kids just want people to talk to them to distract [them]. That's where the individualised planning that I like will come into place."

"I don't need to fit everyone to just one strategy," she shared. "It's about you and what makes you feel most comfortable during the procedure."

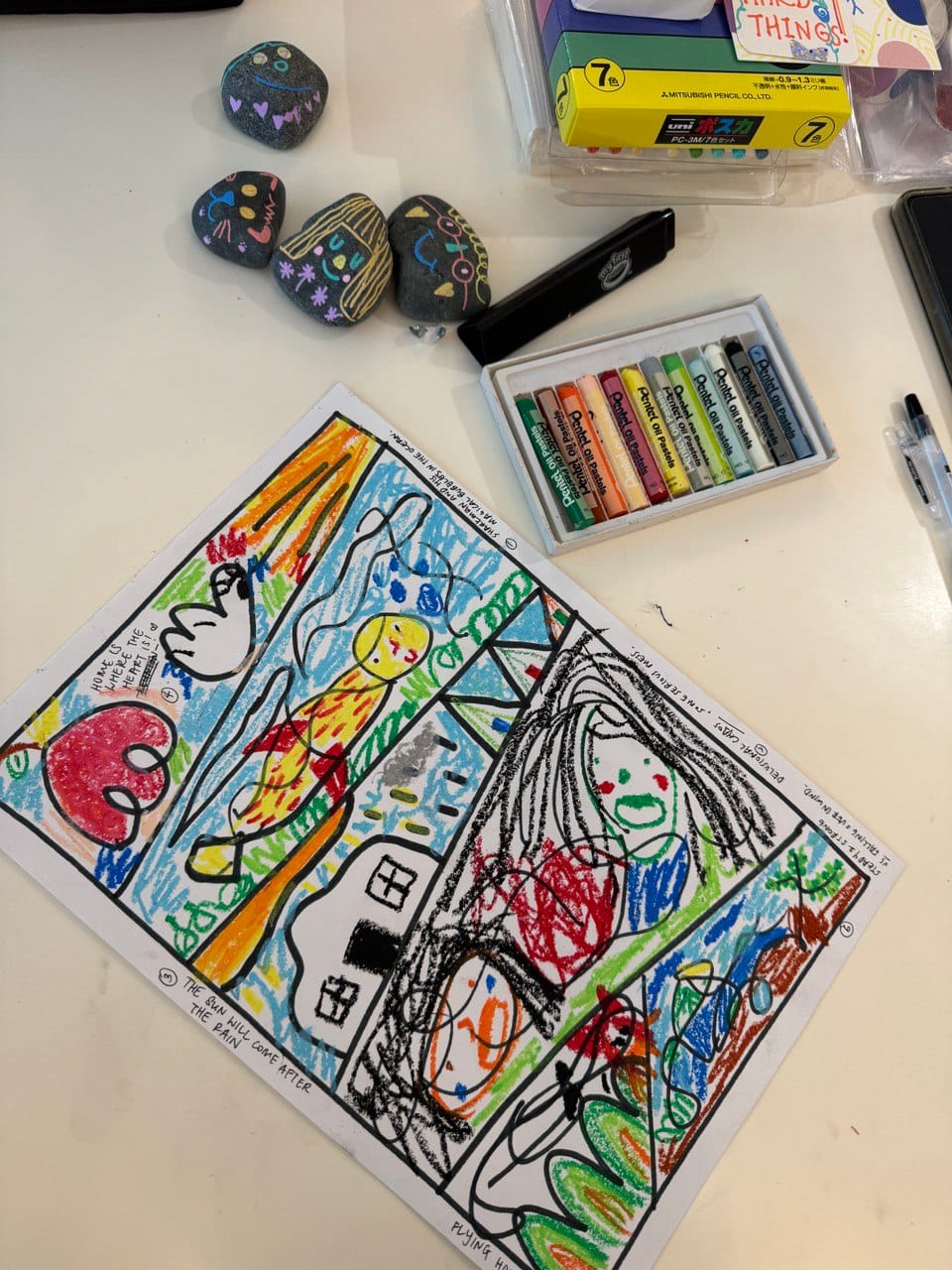

"For older kids, they're able to vocalise, 'This is what will make me comfortable'. We do more of art, music and just therapeutic conversations," Shermaine added. "We use cards to facilitate some of the conversations about grief and loss. They lose a lot more things that we would imagine. Simple things, like diet is being taken away from them. [They have] prolonged dietary restriction... Isolation - because their immunity is low, so [they] cannot go to the school, cannot go out. Basically, it's just home and the ward... Hair loss, especially for our female cancer warriors."

For young children, Child Life specialists focus on helping the children develop trust towards the medical team and increase their comfort with their presence. They teach nurses to inform the children what they are about to do, so the children know the nurses can be trusted. "It's helping them build [a] relationship with the medical team, so that if one day, Child Life is not around or unable to attend to them, they still have that strategy with them to advocate for themselves," she shared.

Working with Parents

As teachers, we have all met anxious parents. Now, imagine anxious parents with sick children in a hospital, accompanied by a life-changing diagnosis. Some parents have also requested for Shermaine to lie to their child about what they are going through. "My ethical consideration is... I cannot lie to a child," she asserted. "So, I'll say, "I'm just curious... How would the children feel if he or she hears differing information from the medical team? After that, we'll highlight the importance of having a trusting relationship. And we'll just put it out there like a food for thought."

"I'll explain to parents that we feel this way because we have a certain conception or misconception about cancer. But for kids, it's just a new vocabulary," she reason." You can decide how you want to explain cancer. You can choose to omit the word death, if you're not ready to talk about it. You can say cancer is just being sick."

"We always advocate for parents not to lie or hide about it, because we want parents to remain as the trusting figure in a child's life."

"It's also helping parents to regulate. Medical play about helps parents know exactly what is happening, because some of the procedures parents are not allowed inside. So, parents might be very anxious... and sometimes, they might rub the anxiety on the child... A dysregulated parent will have a dysregulated child. So, sometimes, when we play, we try to invite parents along. And then, they are also equipped with the skills to continue with the play when they go home... They have more capacity to meet the children's needs; they are co-regulating each other."

However, there are times this is easier said than done, especially when parents have not come to terms with the situation themselves, and her interactions with patients touch on a sensitive subject. As respecting a patient's privacy and confidentiality plays a huge part in her interactions with parents, Shermaine has to walk the tricky line between keeping her conversations with the children between just them, but also answering their parent's questions and meeting their needs.

"There were these conflicting ideas... One was ready to talk about death, one is not ready. But [the] child wants [her] mum to know about death," she brought up an example. "How can I then bring the child's points across without telling [the] mum what exactly happened during the session? There are a lot of ethical considerations, and that's where you realise where your beliefs and values are at."

When I asked if her priority is always what the child wants, Shermaine shakes her head, too. "To a certain extent," she explained. "Because if the children doesn't want to eat [their] medicine, I cannot fulfil that. So, that's where we build negotiable and non-negotiable boundaries. I will always give them options."

"There're a lot of things that are beyond their control; I will try to give them some control... in such a powerless environment."

"I speak to parents every other day, so the way I carry myself, the knowledge that I have that I'll transfer to them. I think that comes with a lot of practice and preparation, which I wouldn't be able to [do], if I haven't had that experience work as a teacher," she reflected.

Linking Early Childhood Education and Child Life

Shermaine and I were thick as thieves back in SUSS—we enrolled and graduated in the same year following our diploma, and never left each other's sides. Reflecting on what we've learnt in ECE brought back fond memories for me, and it was just as interesting to see how she's applying her knowledge in different ways.

"I think there are a lot of different theories that we rely on. And [I] see the theories come to life even when I'm not in a classroom setting," she remarked. "We have Erikson's theory, Maslow, we have Bronfenbrenner. So it's, like, all these theories kind of make sense. And we also see how children regress. Maybe, like, a 4-year-old suddenly [would] emotionally regress back to thumb sucking, cannot sleep alone, not toilet trained..."

"When we see all of these behaviours, we kind of know that the emotional capacity is beyond what the child can cope with, so the child then regresses back to where a safe base is at," she said. "That's where we have to rework on... the developmentally appropriate activities or strategies to help the child feel confident again in such a foreign environment."

This information was new to me, but made so much sense. "That's interesting," I told her, "Because, as teachers, you never really see regression that much... It's day to day that they are in school; there'll always be some kind of progress."

"Yeah, regression happens quite a bit," she replied. "Once a child goes through a huge change, like surgery or a very traumatic experience at the A&E; maybe they were rushed in by ambulance... We see the child kind of, like, withdraw a bit... But the thing is there're no words from the children. So these are all the behavioural indicators during our intake assessment."

Taking these experiences into account, Shermaine reflected that child observation became an important skill she took from the ECE program at SUSS. "Once you know the age of the child, you kind of can quickly put some of the typical behaviours that you see in a childcare setting... That forms my baseline assessment... So, I guess having a strong understanding of children.. and different stages of play works."

"Planning for activities, too," she remarked. "Age-appropriate activities has helped a lot. For kids who are prolonged here for a long period, I will do developmental play with them; helping them meet some of the milestones."

Death as a Part of the Job

Another unique aspect about Shermaine's job is her interactions with death, something we don't come across very often, if at all, in the classroom.

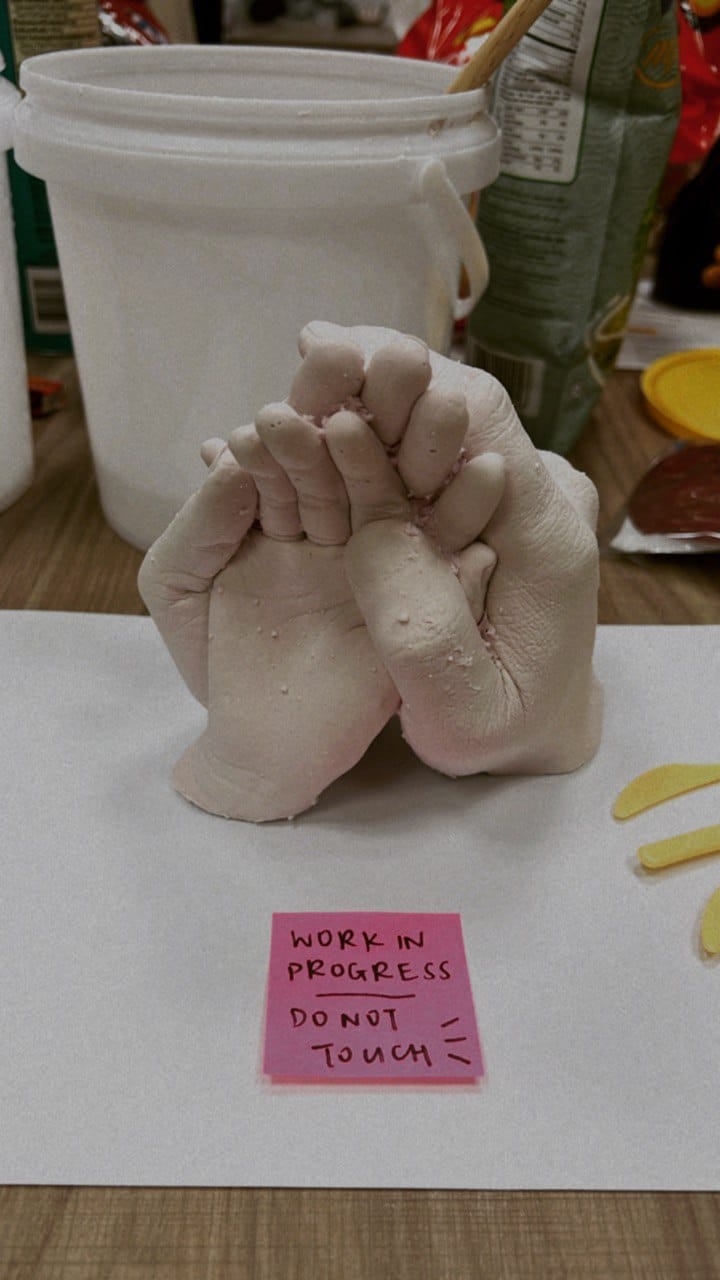

"There's a very precious relationship that I get to share with patients, that I don't think can be formed in the a classroom. You can still have a therapeutic and very supportive relationship in classroom, but not to the extent when I work with palliative patients," she shared. "I think the last few moments is something that I cherish the most."

"It's so valuable to be able to journey with someone through their last moments of their life. It's not like the last moments of K2, it's really an end of life," she reflected. "I think it gives me a lot of insights as to what life and death is all about."

"You know, some kids can be really scared of death. Some kid just think that, 'Oh, when I die, I'll be an angel. I'll go and play with the clouds and rainbows.' I guess helping them to overcome that fear of death, if they have any, through the use of books, memory making... giving them a legacy to leave behind..."

"Legacy building focuses on strength: If you were to leave the world, what would people remember you for?" she explained. "Some kids do art exhibitions to showcase their artwork and raise funds. Some kids do music... It's really the palliative patients that I'm most xing-teng [tender-hearted] about. It's very real that they are not there."

"They have an impact in my life, I guess. That's where I get the most out of the entire relationship, because not everyone gets to be there for you... Part of me is just very appreciative of life... It's like, 'Thank you for allowing me to do this with you. You must be so proud of yourself.'"

Hopes & Dreams

"Not having awareness about this role in this hospital can be quite challenging. That's where my team and I have to constantly send out emails to build rapport with other departments," Shermaine shared. "[I hope] to raise awareness, to expand the team, so that every hospital can have our own Child Life team."

"Not just the paediatric hospitals, because... what about the children who get into road accidents and they are rushed to the nearest hospital, but it's not NUH or KKH?... So, we need to raise awareness and and train more people at different hospitals or even polyclinics," she asserted. "In the States, courts and even dental clinics, they are very child-friendly. Child Life specialists are so common there."

For anyone thinking about going into Child Life, you can probably guess that the emotional load of this work can be heavy. "You cannot detach yourself from the emotions... Would you be ready to talk about certain difficult topics?... Prioritise yourself first, know your strengths and weaknesses...

"I hope more people have the emotional capacity and the compassion to be in the field."

Shermaine, thank you for taking the time to sit down and chat with Circle Time (I mean, not like you really had a choice - HA!). We can't wait to see how the Child Life field grows and expands. Here's wishing you all the best!